A Turning Point for Climate Action: The International Court of Justice’s Advisory Opinion on States’ Obligations

Climate change is an existential problem of planetary proportions that imperils all forms of life and the very health of our planet. [1]

God gave Noah the rainbow sign, no more water, the fire next time. [2]

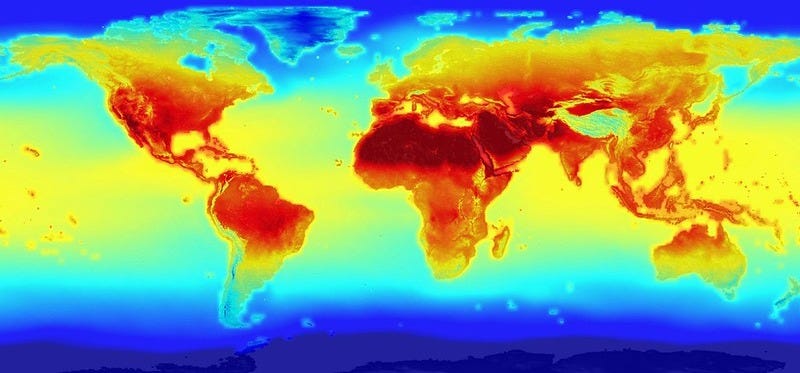

In late 2025, the signs of climate breakdown are impossible to ignore. In Bangladesh and Pakistan, monsoon flooding has displaced hundreds of thousands. Wildfires have scorched over 20 million acres across Canada, sending toxic smoke as far south as New York City. Southern Europe endured its third consecutive heatwave, with temperatures topping 115 degrees Fahrenheit and infrastructure buckling under the strain. Drought grips the Horn of Africa.

These aren’t isolated events—they’re symptoms of a global crisis that is reshaping borders, economies, and societies. Climate change is driving mass internal and cross-border migration, straining housing systems, and fueling resource conflicts. Governments are grappling with food insecurity, energy instability, and the erosion of public trust as climate shocks outpace institutional responses.

This is no longer just a scientific or policy challenge—it’s an existential emergency.

On March 29, 2023, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) adopted a resolution asking the UN’s highest court, the International Court of Justice (ICJ), to provide an advisory opinion on the legal obligations of States to address the challenges of climate change. [3]

In response to the UNGA’s request, on July 23, 2025 the ICJ issued a groundbreaking advisory opinion that reframes responses to climate change as a matter of governmental obligations and provides new legal support for climate action. States, the Court affirmed, are bound by several sources of international law to prevent environmental harm, protect human rights, and safeguard the planet.

This article breaks down the ICJ’s core findings, legal implications, and global impact—and why this moment could redefine climate accountability for decades to come.

Sections of This Article

I. Core Findings

II. Sources of International Law That Support ICJ’s Advisory Opinion

III. Legal Consequences Arising From Breaching A State’s Obligations

IV. Why It Matters

V. Conclusion

Core Findings

For the first time, the ICJ declared that climate inaction by States is not just irresponsible—it’s unlawful. The Court concluded that:

States have legal obligations to protect the climate system under international law.

States are required to exercise due diligence to take all appropriate measures to prevent significant environmental harm, informed by the best available science and guided by the “precautionary principle”—which means acting to prevent serious or irreversible damage even when scientific certainty is incomplete.

Customary international law obliges States to prevent transboundary harm, conduct environmental impact assessments, and cooperate to mitigate climate risks.

Human rights law applies to climate harm; States must safeguard the internationally-recognized human rights to life, health, and a clean environment when implementing climate policies.

Private sector accountability: States cannot ignore corporate emissions. The ICJ stressed that States have a due-diligence obligation to regulate private actors whose activities impact the global climate system. Failing to legislate, administer, and enforce effective emission limits can trigger State responsibility.

Developed countries have special responsibilities that stem from both historical emissions and greater financial and technological capacity to mitigate and adapt to climate impacts. Those with greater resources and historical contributions to the problem must do more.

States’ failure to adopt meaningful climate commitments may amount to an internationally wrongful act.

Legal consequences in the event a State is found to have committed an internationally wrongful act include mandatory cessation of the harmful conduct, committing to guarantees of non-repetition, and making reparations to affected States and communities.

These obligations are erga omnes—owed to the international community as a whole, not just to directly affected parties.

Sources of International Law That Support ICJ’s Advisory Opinion

This section drills down to explain States’ obligations under each of the main bodies of international law invoked by the ICJ in its advisory opinion.

1. States’ Treaty-Based Environmental Obligations

The Court confirmed that States must honor commitments made under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (NFCCC) and the Paris Agreement by acting with due diligence to mitigate emissions and adapt to climate impacts.

Under the Paris Agreement, States must:

Submit progressive and successive nationally determined contributions (NDCs) that are capable—collectively—of limiting warming to 1.5°C;

Take domestic measures reasonably capable of achieving their NDCs; and

Cooperate in good faith through finance, technology transfer, and capacity-building.

2. States’ Obligations Under Human Rights Law

In 2021 and 2022, after a years-long campaign by vulnerable nations and civil society, the UN’s Human Rights Council and the UNGA both adopted resolutions recognizing the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment as a human right. See my post here.

The most interesting part of the ICJ’s advisory opinion is how it draws on existing human rights treaties to find that States have obligations to protect, prevent and mitigate the effects of climate change under the international human rights regime. The ICJ’s advisory opinion affirmed that States’ climate obligations are inseparable from their duties to uphold fundamental human rights.

“[T]he full enjoyment of human rights cannot be ensured without the protection of the climate system and other parts of the environment.” [4]

In so ruling, the Court referred to several key international human rights treaties as sources of law that impose climate-related obligations on States, including:

the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights--recognized for protecting the right to life, which the Court affirmed is directly threatened by climate-related harms such as extreme weather, sea-level rise, and ecosystem collapse;

the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights--cited for its protections of the rights to health, adequate food, water, and housing—all of which are undermined by climate change;

the Convention on the Rights of the Child--highlighted in relation to the disproportionate impact of climate change on children, especially in vulnerable regions;

the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women --referenced to underscore the gendered dimensions of climate harm and the obligation to protect women’s rights in climate policy and adaptation efforts; and

the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities--used to affirm that climate policies must be inclusive and protect the rights of persons with disabilities, who often face heightened risks during climate disasters.

Regional Human Rights Instruments. The ICJ also drew on jurisprudence from regional courts, including the European Court of Human Rights, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, and the African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights, all of which have recognized environmental degradation as a human rights issue.

The opinion reframed climate inaction as a breach of legal obligations under these human rights treaties, not just environmental ones. The Court emphasized that States must integrate human rights considerations into their climate policies and treaty implementation:

“States must therefore take their obligations under international human rights law into account when implementing their obligations under the climate change treaties and other relevant environmental treaties and under customary international law.” [5]

This dual obligation—rooted in both environmental and human rights law—strengthens the legal basis for holding States accountable for climate harm that affects life, health, and dignity. It also aligns with the growing recognition of the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment as a universal human right.

By grounding climate obligations in human rights law, the ICJ opened new avenues for litigation, advocacy, and treaty reform. It empowered affected communities and civil society to challenge insufficient climate action not only through environmental channels, but also through human rights mechanisms.

3. States’ Obligations Pertaining To Oceans and Sea-Level Rise

The ICJ found that under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), States have a duty to protect, prevent and preserve the marine environment from adverse climate impacts such as ocean acidification, sea-level rise, and biodiversity loss caused by greenhouse gas emissions. It concluded that States must act with due diligence and cooperate to mitigate these harms, interpreting UNCLOS as imposing proactive duties to regulate emissions and support adaptation efforts, especially for vulnerable coastal and island nations. This interpretation reinforces the view that climate-related marine degradation is not just a scientific concern but a breach of binding international law.

4. States’ Duties Under Customary International Law

Beyond treaty commitments, the ICJ found that States are also bound by customary international law, which imposes binding obligations derived from consistent state practice and a shared sense of legal duty. These norms apply universally—even to States that are not party to specific treaties—and they form a critical legal foundation for global climate accountability. [6]

Under customary international law, States must:

Prevent significant transboundary harm to the climate system, applying a rigorous due diligence standard that reflects the best available science and the precautionary principle. This means taking proactive measures to avoid foreseeable environmental damage, even in the face of scientific uncertainty.

Conduct environmental impact and risk assessments, including consideration of the cumulative effects of their actions and omissions on the climate system. This duty ensures that States account not only for isolated emissions but for the broader consequences of their development choices and regulatory gaps.

Cooperate continuously and in good faith to avert climate harm, including through data sharing, joint mitigation efforts, and support for vulnerable nations. Cooperation is not optional—it is a legal expectation embedded in the fabric of international environmental law.

These obligations are recognized as erga omnes duties—owed to the international community as a whole. Their breach may constitute an internationally wrongful act, triggering legal consequences under the law of state responsibility. The ICJ’s advisory opinion reinforces that customary norms are not abstract ideals but enforceable standards that shape how States must act in the face of escalating climate threats.

The ICJ’s opinion is a masterclass in legal synthesis—it didn’t just cite these bodies of law in isolation, but wove them together to show that climate harm is governed by a unified framework of enforceable obligations.

Legal Consequences Arising From Breaching A State’s Obligations

The ICJ found that failures to comply with these obligations may constitute internationally wrongful acts, triggering: obligations to cease the wrongful conduct, provide assurances of non-repetition, and make full reparation where the harm is direct and certain.

This term comes from the law of State responsibility, as codified by the UN’s International Law Commission. [7] It refers to any act or omission by a State that:

Is attributable to the State, and

Breaches an international legal obligation.

Importantly, the act doesn’t need to be intentional—it can result from negligence, failure to act, or inadequate regulation. In the climate context, the ICJ clarified that inaction or insufficient climate measures, such as weak emissions targets or failure to cooperate, may constitute internationally wrongful acts if they violate binding obligations.

This opens the door to legal claims before the ICJ or other tribunals, especially by vulnerable nations suffering climate harm; and heightened scrutiny in domestic courts where judges may now treat climate inaction as a breach of binding international norms.

Labeling climate inaction as an internationally wrongful act also shifts the diplomatic tone. It reframes climate negotiations from voluntary cooperation to legal accountability. States can no longer hide behind vague pledges or economic excuses. Instead, they may face reputational damage for knowingly violating international law; pressure from civil society and international organizations to comply with their obligations; and increased vulnerability to litigation, including investor-state disputes and human rights claims.

Why It Matters: The Impact of the ICJ’s Advisory Opinion

The ICJ’s advisory opinion is not enforceable. Its significance lies in its power to shape norms, influence behavior, and legitimize demands for accountability.

Advisory opinions are often described as “soft law,” yet in practice, they serve as authoritative interpretations of existing legal obligations. In this case, the ICJ clarified that States have duties under customary international law and treaties to prevent environmental harm and protect future generations. That clarification now becomes a touchstone for courts, legislatures, and civil society worldwide.

For climate advocates, the opinion offers a new legal vocabulary—and a moral compass. It affirms that climate change is not just a technical or economic issue, but a justice imperative rooted in international law. In this respect, the opinion adds support for the local, national and regional lawsuits brought by youths, nations particularly vulnerable to the ravages of climate change, indigenous groups and other segments of civil society using the courts to spur climate action and to seek climate justice.

Courts often look to ICJ opinions when interpreting ambiguous treaty provisions or assessing State responsibility. Already, legal teams in countries from the Philippines to the Netherlands are citing the ICJ’s advisory opinion to bolster cases against governments and corporations that fail to meet climate obligations. While the ICJ cannot enforce compliance, it has effectively armed the global climate movement with a legal shield and a rhetorical sword.

The opinion also exerts pressure on policymakers. Governments that have resisted ambitious climate action now face heightened scrutiny—not just from activists, but from their own legal advisors and international peers. The ICJ’s framing of climate harm as a violation of human rights and intergenerational equity raises the stakes for inaction. It invites parliaments to codify stronger climate laws, compels ministries to revisit mitigation and adaptation plans, and emboldens small island States and vulnerable nations to demand reparations and support. In diplomatic circles, the opinion is already influencing treaty negotiations and multilateral funding frameworks.

Finally, the ICJ’s opinion matters because it shifts the narrative. It validates the lived experience of communities on the frontlines of climate disruption—those displaced by rising seas, scorched by wildfires, or starved by drought. In doing so, the Court has elevated climate justice from the margins of international law to its very center. And while enforcement may be elusive, the legal legitimacy conferred by the ICJ is a powerful force—one that can reshape norms, galvanize action, and hold power to account.

Conclusion

The ICJ’s advisory opinion makes clear that the suffering and disruption caused by climate change is not just collateral damage—it is a breach of States’ legal duties. The Court acknowledged that it will take more than a legal opinion to meet the challenges of climate change:

“A complete solution to this daunting, and self-inflicted, problem requires the contribution of all fields of human knowledge, whether law, science, economics or any other. Above all, a lasting and satisfactory solution requires human will and wisdom — at the individual, social and political levels — to change our habits, comforts and current way of life in order to secure a future for ourselves and those who are yet to come.

Through this Opinion, the Court participates in the activities of the United Nations and the international community represented in that body, with the hope that its conclusions will allow the law to inform and guide social and political action to address the ongoing climate crisis.” [8]

However, the opinion is more than a legal document—it is a compass for climate justice. It equips advocates, lawmakers, and jurists with a powerful tool to accelerate social and political action. It is now for us to use that tool in all fields to advance climate action.

Read the full advisory opinion here or the summary of the opinion here.

Footnotes

International Court of Justice, Obligations of States in respect of Climate Change, Advisory Opinion of 23 July 2025, ICJ Rep. 2025, para. 456 (English)

From an African American spiritual that warns of divine judgment.

The request for an advisory opinion on climate obligations was initiated by the Pacific island nation of Vanuatu, driven by youth-led advocacy and legal scholars concerned about climate threats. Vanuatu was joined by over 130 other countries, and a core group of nations including Antigua & Barbuda, Costa Rica, Germany, Samoa, Bangladesh, and New Zealand, many of which are existentially threatened by sea-level rise and other consequences of climate change.

ICJ Advisory Opinion (2025), para. 403 (English)

ICJ Advisory Opinion (2025), para. 404 (English)

Customary International Law consists of binding norms derived from the consistent and general practice of states, accepted as law (opinio juris). Unlike treaty or statutory law, which is formally codified through written agreements or legislation, customary law emerges organically over time and applies even in the absence of explicit written consent.

International Law Commission, Draft Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 2001, vol. II, Part Two, UN Doc. A/56/10.

ICJ Advisory Opinion (2025), para. 456 (English)